Who has access to the data that can best predict how readers will spend their money? Who has data on how people read books—how far they get, how many they buy, how often they buy, whether their purchases cluster around certain dates? Who has the permission to contact readers by post, email or text—to shape their opinions and buying patterns?

Who, in other words, owns the data that holds the key to publishing’s future performance?

Back in the day, I worked as a retail buyer. My vendors included P&G and Unilever — companies that spent decades putting the processes in place to collect and use customer data. And not just transactional data: insights, research, coupon data, mailing lists, free samples in exchange for personal data, focus group data. Massive, detailed, long-term use surveys. They were the sort of companies that paid for eye-tracking research to understand how shoppers shop, and which bits of the shelves they looked at most. They were the sort of companies that sent reps around maternity wards, signing up new mothers to their mailing lists with the lure of free Pampers, then mailing them coupons and samples for Colgate five years later. They invested because they knew that owning customer data gave them power—power to persuade retail buyers that they needed to include their brands in categories on-shelf, because they could prove that there was demand. Power to know the retail price sweet spot. Power to disintermediate retailers entirely, if they wanted. And because everyone knew they could, they didn’t have to.

Retailers go through cycles of grumbling about this process and then embracing it. The strategic sourcing and merchandizing approach known as category management came about because retailers wanted to use their vendors’ customer knowledge to improve their own performance. But back in publishing, we’re barely trying to gain control of our customer data.

We’re the vendors, and Google, Facebook and Amazon are the retailers. And in our world, it’s retailers who have the balance of power. Not brick-and-mortar ones—obviously. They’re still as fundamentally short-termist, reactionary and focused on this quarter as they ever were. Don’t expect us to be impressed with a tired old loyalty card scheme, either—especially if you execute it badly, as we saw in the supermarket sector in the UK, recently, when Lidl delivered a stern riposte to Morrison’s clumsy data collection. No, it’s the new retailers who are the ones investing the time and money in gathering and using transactional and behavioral data.

They collect transactional and click data from every interaction on their website and email marketing lists, and use it to give customers what their data suggests they want: recommendations, bundled up-selling deals, predictions to inform new product development, all based on individual customer data going back 20 years. Compare the power that this gives them with the power we have. When we sell books to the parts of the supply chain that we focus on—the wholesalers and retailers—they disappear off the radar. We have no idea whether books are going to stay in a wholesalers’ warehouse, whether they’re in Waterstones’ central warehouse or on the shelf, and we certainly have no idea which readers bought them, from where, or what happened to them.

We don’t have to sell directly to gather meaningful data (the old consumer goods manufacturers prove that). But it makes it so much easier and cheaper if we do. With platforms like Google Analytics and Shopify, nowadays we can collect insightful data, such as abandoned carts, over- and under-performers, IP addresses, flow of clicks through the site, sources of traffic and the results of marketing campaigns at practically zero additional cost. We could be orchestrating more meaningful, structured, long-term interactions with readers who use the brick-and-mortar supply chain—not just ad hoc social media interactions and marketing campaigns.

But it’s so much better to aim to own the cart. That’s the key. If you hand sales off to someone else, then you have no idea whether they bought it, or where they live, or what else they bought. You have to own that. And you have to make things cheap (both the product and the technology) so that people will use it.

Take a look at pretty much any major publisher’s website. This large publisher can’t sell ebooks or audiobooks from its website, although they’re far from alone. They don’t know how much retailers are charging, and they don’t even know the retail price of their own imprint’s book:

Hachette has it at £8.99, whereas Hodder has it at £7.99. What can their systems architecture look like, I wonder?

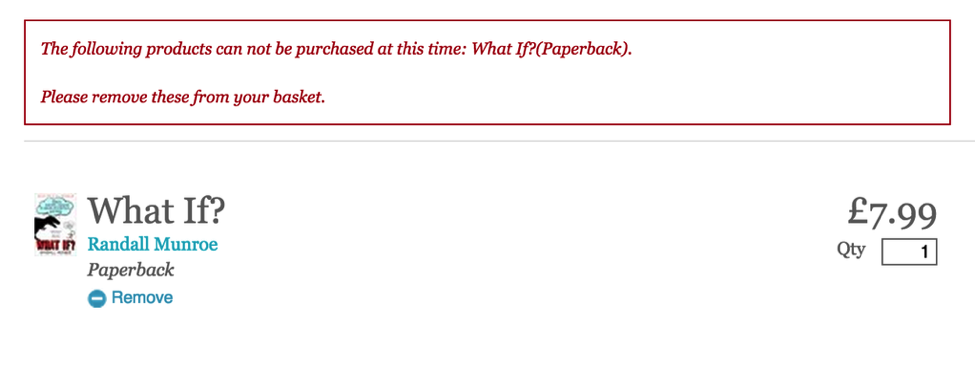

If you do decide to buy the paperback version from them, then you have to manually choose what country and county you live in, even though they have a really nice way of looking up your address that makes that logically redundant. And then, after registering on the site and handing over your address, phone number and email, you get this:

Only their shopping cart knows the stock level.

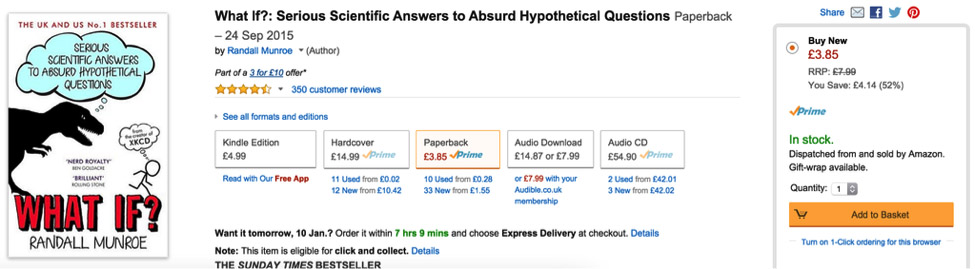

Or I can buy it on Amazon Prime right now for £3.85:

Why don’t publishers fix this problem and try to regain the balance of power? Simply put, it’s because they don’t equate customer and transactional data with control. And even if they did, they’ve had no practice in acquiring and managing large data sets. They wouldn’t know where to start if they had to create a supply chain of any complexity. You wouldn’t believe the conversations I still have with some publisher-owned distribution companies about data transfer and management. They’re a good 30 to 40 years behind the modern world. Large parts of the supply chain rely on CSVs, emails, spreadsheets and EDI, not well-crafted databases, RESTful JSON API calls and webhooks.

Publishers’ own websites provide a poor customer experience. This is no basis for becoming adept at big data management.

So, who has the balance of power? Not publishers—that’s for sure. And I don’t know how we’re going to get it back if we fail to prioritize owning the cart.

Are your current systems sabotaging your growth ambitions? Are you hungry to implement new business models, but concerned you lack the strong administrative foundations needed for innovation?

We're always amazed at how resigned publishers have had to become to the low bar in publishing management systems. Demand more.

Contact us via our contact form, or email us.